Meeting for Worship; Meeting for Business

Not long ago, one of the young interns at the Friends Committee on National Legislation (FCNL) posted a kind of letter of concern to the FCNL interns’ collective blog site, Of Peace and Politics.

Jay’s concern was that the FCNL annual meeting had turned out more like a secular organization’s business meeting than like a Friends meeting for business. The focus of most of the participants, Jay wrote, “did not seem particularly centered”. He added, “The number of “I” statements was rather surprising. Many people were pushing their pet issues, and trying to attach them to the priorities document.”

And Jay wrote that, as the meeting discussed FCNL’s list of priorities, “The question that was asked [by the clerks of the meeting] was, ‘we’ll now open the floor to Friends’ comments, questions and concerns.’ But we’re not looking for individual Friends’ comments or concerns unless those concerns rise to a level of conscience, are we? We’re looking for what Friends are led to do in the next two years with regards to our federal government.” (Emphasis mine.)

Two other Friends wrote in to say that they agreed with Jay’s impressions of the meeting.

Now, from my standpoint as a traditional Friend, these matters are serious indeed.

We qualify as Friends to the degree that we live up to Christ’s charge in John 15:14: “You are my friends if you do whatsoever I tell you.” If we’re not listening to Christ — if we’re all caught up in our own pet issues and opinions, our own heads, as Jay felt was the case with most of the visible and audible Friends at the FCNL meeting — if we’re not willing to lay aside those things, as I laid aside my own pet environmental issues on my walk last summer, so that Christ may instruct and lead us in the way he chooses — how can we do whatsoever he tells us?

And if we don’t do whatsoever he tells us, then we are purely not entitled to the good name of Friends.

All these matters came back to me again this morning. My local monthly meeting was gathered to consider some language that might possibly be used to describe, in the next edition of our discipline, how we Iowa (Conservative) Friends practice meeting for worship.

I hadn’t seen the proposed language previously. It was all new to me! But as I looked the language over, a sense grew within me that something needful was missing.

And after some thought, I began to think that what was missing in the language, was directly connected to what was missing at that FCNL meeting.

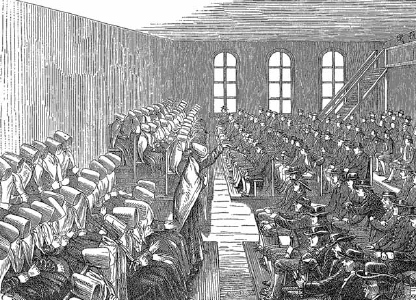

Philadelphia: Quäkerkirche. Wood engraving from Ernst von Hesse Wartegg, Nord-Amerika, seine Stadt und Naturwunder, das Land und seine Bewohner in Schilderung (Leipzig: 1888). General Collections, Library of Congress.

The language before us, described our Quaker worship process as one in which we “quiet our senses and center down” so as to “approach the spiritual center of the Meeting” and “sense a greater nearness to the divine source of all truth and reality”.

As far as it goes, this is good language, no question. But it fails to remind us of how worship can and must connect to the divine imperative in our hearts — the imperative that, as we soon discover, overwhelms all our own pet projects, all our own hopes and fears and ideas, indeed overwhelms us altogether, and thereby transforms us: from self-led activists to willing servants, and from individualists to members of the team.

Friends lined up to speak at the microphone at the 2006 FCNL annual meeting. Notice the many differences in group dynamics from the scene in the woodcut above. This photo is reproduced from Jay’s essay on the FCNL interns’ web site.

The language of the Discipline Revision Committee portrayed what we do as “silent worship”. But what transforms us is not silence; it’s practice in waiting upon the Lord.

The very act of waiting, as a waiter waits on a customer, or a courtier on a king, is practice in setting aside one’s own ideas and opinions and learning to serve. Six months of hour-long waiting worship twice a week is the sort of intensive training in setting aside one’s self and learning to serve, that can change a person visibly. Six months of hour-long sitting in silence twice a week, seeking for truth and reality, may never once take a person beyond thinking that he knows the truth better than anyone else around him.

I was moved to share with my meeting a quotation from the writings of our old Friend Isaac Penington, which is the one of the oldest systematic descriptions of how Friends practice meeting for worship that I know:

…This is the manner of their worship. They are to wait upon the Lord, to meet in the silence of flesh, and to watch for the stirrings of his life, and the breakings forth of his power amongst them. And in the breakings forth of that power they may pray, speak, exhort, rebuke, sing, or mourn, &c., according as the Spirit teaches, requires, and gives utterance.

But if the Spirit do not require to speak, and give to utter, then every one is to sit still in his place (in his heavenly place I mean), feeling his own measure, feeding thereupon, receiving therefrom, into his spirit, what the Lord giveth. Now, in this is edifying, pure edifying, precious edifying; his soul who thus waits, is hereby particularly edified by the Spirit of the Lord at every meeting.

And then also there is the life of the whole felt in every vessel that is turned to its measure: insomuch as the warmth of life in each vessel doth not only warm the particular, but they are like a heap of fresh and living coals, warming one another, insomuch as a great strength, freshness, and vigor of life flows into all.

And if any be burthened, tempted, buffeted by Satan, bowed down, overborne, languishing, afflicted, distressed, &c., the estate of such is felt in Spirit, and secret cries, or open (as the Lord pleaseth), ascend up to the Lord for them, and they many times find ease and relief, in a few words spoken, or without words, if it be the season of their help and relief with the Lord.

For absolutely silent meetings, wherein there is a resolution not to speak, we know not; but we wait upon the Lord, either to feel him in words, or in silence of spirit without words, as he pleaseth.

— Penington, A Further Testimony to Truth Revived Out of the Ruins of

the Apostasy… (published posthumously in 1680)

I would ask you, friends and readers, to consider several parts of this passage especially.

To begin with, I would ask you to notice how Penington calls us specifically to “watch for the stirrings of his life, and the breakings forth of his power amongst them.” This helps us better understand what early Friends meant by “waiting”.

I would ask you to notice how Penington says that these breakings forth of God’s power lead us to speak, pray, exhort, rebuke, etc., “according as the Spirit teaches, requires, and gives utterance.” This helps us focus on what early Friends meant by the Spirit: it is not just a feel-good thing, but a source of imperatives in our lives. The Spirit is such that, when we listen to it, we feel, this is what I/we must do to restore goodness and kindness in this situation, or, this is what I/we must do to inspire one another, or simply, this is what I/we must do to love one another, to make one another feel cared for, as God also loves us and makes us feel cared for.

And finally, I would ask you to notice and think about Penington’s metaphor of the living coals. I’m sure, if any of you have ever cooked over a wood or charcoal fire, you know that a single stick or lump of coal will cool and burn out before it is completely consumed, but two or more sticks or lumps will reflect heat back and forth and keep each other burning, and a heap of coals will reduce itself completely to ash. This is what meeting for worship does for us — and if it fails to do it for us, it fails because we are too self-absorbed to reflect the love back and forth between us and so keep one another burning.

Meeting for business is simply meeting for worship with a fistful of collective petitions to present to the King. Properly practiced, it differs from meeting for worship in no other way.

And meeting for worship, similarly, is just meeting for business deprived of the collective petitions. It may still have individual petitions — matters that individual worshipers lay before the king in prayer. But no group petitions. And that’s really the only difference.

Thus it is silly to call meeting for business, “meeting for worship for business”, as if the meeting for worship were something more basic than the meeting for business. They are both equally un-basic. What’s basic is waiting on the King.

Meeting for business is waiting upon the King with collective petitions to lay before Him; meeting for worship may be no more than waiting on the King’s pleasure. But either way, the “stirrings of his life and breakings forth of his power”, which Penington refers to, might be compared to royal nods and gestures that the good courtier, waiting, rejoices in his heart to see, and leaps to obey.

If we understand that, and put it into practice, then problems with business meetings that don’t feel like business meetings, simply will not arise.

But what this means is that we have to get into the habit of teaching one another, and teaching the newcomers in our midst, how to practice waiting on the Lord.

I don’t yet know how we might do that in the next edition of our yearly meeting discipline. But it’s something my little meeting has agreed to think about.

Reader Comments (13)

How then shall a lonely coal lump wait upon the Lord?

Hi, david!

Waiting on the Lord is practiced the same way whether one is alone or in a group, and whether one is surrounded by silence or by uproar.

Waiting on the Lord, and being obedient to Him, is the vertical component in the cross that Friends take up. What meeting for worship and for business, and all the community life of a Friends meeting, have to offer, that solitary worship cannot match, is the horizontal component. It is precisely when we are at the place where the horizontal and vertical components of the cross intersect, that we most clearly and strongly experience living in Christ.

But there are other ways to find the horizontal component. For example, we can find it in serving others in humility, as Francis of Assisi did even before followers gathered around him -- letting ourselves be informed and corrected by feedback from those we try to serve. We can do this whether the ones we serve are our fellow believers or not.

And we can generally find companions for waiting worship if we ask. Have you tried organizing a waiting-worship circle in the church you're attending? Or have you tried inviting the neighbors where you live?

But I think you really do have to find the horizontal component somehow -- whether it is in an established meeting, or by starting your own worship group, or through conscious and sustained service to others. As Lloyd Lee Wilson has observed in another context, the solitary Quaker is an oxymoron.

Hey Marshall

I really like this post. It addresses something that's been with me for a while now too.

I'm trying to restrain myself from the tendency to launch into something about how nontheists can do what you're talking about as easily as christians, and that being a christian doesn't mean you will be better at it. But you didn't actually make the claims here that I'm drawn to refute, so perhaps I should just move on to more important things.

I wonder how it's different for you to "wait on the lord" than it is for me to open myself to the fullness of nature and reality.

I'm not talking about pondering or philosophising, the practice feels more "spiritual" than that.

But I do have a problem with imagery and metaphor that depends on serving a king, for example. I even have problems with the passage you quote - I don't think one is a true friend if you do what your friends tell you, then one is a vassal or a servant. I have always been confused by that sentence. True friends also call you on stuff when they believe that you've lost your way, or are in danger of it.

I suppose perhaps that's where the difference lies between christians and non christians. I don't believe that Jesus had a sort of perfect access to the Truth, I just believe he was a wise prophet, so I don't look to him, but directly to the truth.

As for whether it's fuzzy, or hard to access, it is! I believe this is true whether you conceive of "it" as the will of God or as nature, truth, the best possible outcome, etc.

I do concede that I think it might be harder to get to this place (openness to truth) if you conceive of it as a disinterested non-party, rather than a being that actively wants good for the world, but I don't believe that it's impossible to give up your own ego unless you are giving it over to another. From how I read your writing I think that you do believe that, do you?

peace

Pam

Dear Pam,

It's always a pleasure to hear from you.

And as always, you raise a wonderful range of issues. But for brevity's sake, I must limit myself to addressing just three of them in this reply --

First, you raise the the question of whether nontheists can practice "waiting worship" as easily as theists. You write, "I'm trying to restrain myself from the tendency to launch into something about how nontheists can do what you're talking about as easily as christians, and that being a christian doesn't mean you will be better at it."

I'm not sure that you really succeeded in restraining yourself there. But in any case, the assertion you're making isn't true. A nontheist cannot possibly wait upon impersonal truth and reality in the way that a waiter waits on a customer, or a courtier waits on a king.

Well, and why not? It's because the "waiting" relationship, which a waiter has with a customer, or a courtier with a king, is not a relationship between a person and an object, the way "contemplation", "opening oneself up", or "centering" can be. The waiter at a restaurant who contemplates his customers, or opens himself up to them, or centers on them, instead of actively waiting on them, is going to get himself fired!

No relationship can be truthfully described as a waiting relationship, if the one supposedly being "waited upon" is incapable of putting the waiter or courtier to any test by expressing unexpected desires at unexpected moments. And truth and reality, being abstractions rather than people -- and observer-defined abstractions at that! -- are incapable of putting the waiter to such a test. They cannot unexpectedly send the wine back because they don't like it, or unexpectedly change their minds about which entrée they wish to order. Jesus can do such things, God can do such things, but truth and reality cannot.

The person who attempts to wait upon truth and reality may seek to submit to truth and reality, but truth and reality will not actively pressure the person to submit as an unhappy customer can and will do to a waiter, or a king in a courtroom to a courtier. The physicist struggling with results from an experiment, or the politico struggling with a political reality, may find the materials she or he is dealing with uncoöperative, and even daunting, but the materials won't suddenly and out of the blue tell her or him to stop drinking coffee or to quit her job and take up medicine. A customer at a restaurant, on the other hand, or a king on his throne, might easily do such things; and so might God.

You may open yourself to the fullness of truth and reality. And truth and reality will wait for you to do so. But a waiter, a king, or God, won't wait for you to do so. A waiter, a king, or God, will make what demands he pleases when he sees fit, quite regardless of whether you're ready.

Truth and reality won't suddenly say to you, "Go forth, and stand upon the mountain before Me." (I Kings 19:11) Or, "Get yourself out of your homeland, and away from your kinfolk and your father's house, to a land that I will show you." (Genesis 12:1)

-- Or, "You have rightly committed yourself to address Baltimore Yearly Meeting on the subject of the environment, but I still will not permit you to have anything at all to say to them -- unless you humble yourself before Me by walking across the country to where they will meet; and then you must say what I give you along the way" -- which is what happened to me a year and a quarter ago.

A person can make demands of such an arbitrary and outwardly unnecessary character, but truth and reality cannot.

And that, ultimately, is why one cannot "wait upon" truth and reality the way one can wait upon a human being, or upon God.

Second, dear Pam, you raise the issue of service. You write, "I do have a problem with imagery and metaphor that depends on serving a king...." But whether you have a problem with it or not, that is the nature of your relationship with God: He is in charge, and He won't wait on your permission to do a thing.

When He takes the life from your body, there'll be nothing you can do about it. He's the boss in such matters -- period. The choice of when you wake each morning may be under your own control -- you can set an alarm clock -- but the question of whether you will wake at all is not under your control but His. You may have a problem with that, too; but your having a problem with it doesn't give you any more control.

All of existence depends upon His pleasure.

You write, "I don't think one is a true friend if you do what your friends tell you, then one is a vassal or a servant." But the One who made us, and upon whom our lives depend, was utterly our superior long before any question of friendship began to arise. It's not like friendship with a new-found fellow human being, where we start from a position in which neither has any power over the other and the two sides are rightly seen as equals. The One who has all power over our life and death is entirely in control of us from the get-go, and entirely free to confine His friendship to the bounds of our obedience.

And why would we want it any differently? What He tells us to do is this: "Do what's right. Do what's loving. Do what's nurturing. Do what harms none. Do what opens new possibilities for good." In the Sermon at the Last Supper, Christ couples his statement that, "You are my friends if you do whatsoever I command you," with: "This I command you, that you love one another as I have loved you." Why would we -- why would any rational person -- want to disobey such a command?

What I see you doing, Pam (please correct me if I'm wrong) is objecting to the idea of reins. You don't want to wear reins. Okay. Being a fellow human being, I can understand that feeling perfectly. None of us humans really like to wear reins.

Do you also have a problem with the fact that you also wear the reins of gravity? Perhaps you do. But I imagine you accept the situation gracefully and with pragmatism. You respect gravity moment by moment; you do what you need to do to keep your balance and not fall.

God's reins are a lot more compassionate than gravity's. Unlike gravity's reins, we can refuse to take God's reins upon us (although there will ultimately be consequences to that -- to choosing wrongdoing over obedience -- too).

Choosing the right, choosing obedience to that still, small Voice, is left entirely up to us. Gravity is not so willing as God to leave things up to us! So why should we be gracious and pragmatic about obedience to gravity's reins, and not equally so about obedience to God's? God's reins merely require us to do what is good, right, loving, and fruitful, and avoid all harmful behavior. Do such directives and limitations really offend or chafe you that much?

Finally, you raise the question of transcending the ego. You write, "I don't believe that it's impossible to give up your own ego unless you are giving it over to another." And you then ask what I myself believe in this regard.

You phrase this issue in such a way as to make it an abstract argument: Is it theoretically possible to give up one's ego entirely on one's own, or not? But you and I don't get past our own egos by concluding that it's theoretically possible to do it in such-and-such a way; we get past our egos only by concretely and practically getting past our egos. Right?

So I'm not interested in theorizing about getting past our egos. Theorizing doesn't get us there. I'm interested in how we're actually doing, you and I. I want us to actually get there, dear friend!

And in that respect, I find my attention captured by two statements in this comment you've posted here.

One of these is your statement that "I don't believe that Jesus had a sort of perfect access to the Truth, I just believe he was a wise prophet, so I don't look to him, but directly to the truth."

Now, I have no problem with your looking directly to the truth. I think that's wonderful.

But as to the part about Jesus: Who set you up on the judgment seat, friend, to decide whether he had perfect access to the truth, or was just a wise prophet, or whatever?

Is it not an act of egoism, to presume that you are entitled to sit on that judgment seat and judge anyone else at all -- even just the janitor at the local elementary school, let alone Jesus?

I will leave it to you to decide for yourself whether it is egoistic or not; but I will say: when I judge someone, as I indeed do far too often, it always turns out to be egoistic: this, alas, I have seen in myself, much to my shame and embarrassment.

And the other statement: you wrote about how you "have a problem with imagery and metaphor that depends on serving a king". What is the "I" that has this problem? Is it not the ego, saying, I don't want to submit?

Again, I leave it to you to decide for yourself whether it is the ego or not; I will simply say that the part of me that has problems with serving is my own ego. I've spent thirty-five years in efforts to serve God and others despite my ego's resistance, and my ego still kicks up a fuss each new time a new opportunity to yield and serve presents itself.

Indeed, the whole question of whether I can give up my ego in my own way, on my own steam, without another's involvement, is rather egoistic, when I stop to think about it. "I want to do it my way." Is there anything more egoistic than that statement?

I hesitate to push this matter too far, for I feel that I am in grave danger of judging (and inevitably misjudging) you. You know the whole truth of your own condition; I do not. But I humbly submit that the answer to your real question is very probably contained in the reasons you have for asking it, whatever those reasons may be.

Marshall, thank you for your eloquent and grounded essay, especially for the Penington selection. Oh, that I wasn't conducting such conversations over the internet!

Marshall -

thanks for your in depth response. And you're right, I don't know if I did restrain myself. My hope was to talk about what we have in common. You and I are both doing something, and from my perspective it can work out quite similarly at times (not necessarily with the same exact result, but a similar process) but I think I failed, and did just talk about the nontheist/theist split. It's hard to do what I was hoping to do.

I'm amazed that I missed before the centrality of service and submission to your experience. Apparently we are doing very different things, at least at some level.

I am caught, in my own response to this between wanting to exclaim that one CAN serve the truth (that's a phrase that I've certainly heard) and wanting to proclaim that I have no interest in serving anyone, but only in participating. I tend to think of that as a very quakerly way to look at things - that one can participate in God (as a verb, like love) rather than just serving "him" - and what's more, that it's my position that that is the better choice.

Of course that wouldn't be very ego-free, as you pointed out.

I feel as if we get caught up in words a lot, and in concepts. You point out that it's an act of ego or judgement for me to say that Jesus wasn't perfect, and who set me up as judge and jury anyway? I was, however, responding to a perception that you believe that Jesus is/was perfect (am I wrong?) which is, for better or worse, equally egotistical. Besides which, I did say "I believe" - which is true. Who set me up as judge and jury to voice my own beliefs? I guess God did, or nature, or simply the way things are, and I wouldn't have it any other way.

I also get caught up in phrasing - you took issue with my "I have a problem with" - as if I'm looking at the whole world as if it's all my little bubbble and am incredibly naive. I simply mean that I don't perceive that to be the reality, or perhaps, God's will.

You make proclamations about how God is (he decides whether or not I will wake up tomorrow morning, etc) with no reference to yourself -it's not that you believe that, it's that it's TRUE. That to me comes across as much more egotistical than me simply stating my own belief. (note, perhaps you would be less offended if I said that IS much more egotistical - then my own perception doesn't come into it, right?)

But, in the end, perhaps we are in a different place.

I am left with a question about what you perceive God's will to be. Does God always will the greatest good? The greatest kindness? The fairest outcome? Is God totally random and often jealous and downright mean, like in the old testament? What are you putting your faith into when you commit yourself to God's will? I assume that it IS something - like my favorite color is purple or my favorite fruit is peaches.

And then, if that is true, what if we take that out of the equation and serve it directly. Rather than doing God's will, because we assume it to be for the greater good (for example), why not serve the greater good directly? (or serve life, human dignity, love, compassion, justice, directly)

Please note that I am not suggesting that we serve these things, or determine these things, only with our intellect. I believe that there is a spiritual component to discerning how best to serve these)

If, however, you are only serving God because he's in control and there's nothing you can do about it, that's fine, it's got a grand tradition in human cultures, but it often included throwing virgins or enemies (or virgin enemies?) into volcanoes and such (Okay, I don't know if anyone ever did that, actually)

Similarly, I don't feel frustrated by being "reigned in" by gravity (usually) - but I dont' go out of my way to serve gravity either. And God isnt' a scientifically proven natural law - nor is "he" anything I've ever experienced (explicitly anyway)

Hey Marshall.

I haven't even reread what I wrote, but I do worry that it came across as overly strident or accusatory, or any number of other things.

I am quite sensitive, and passionate on these topics, as you may have noticed,

I also think that I fall into the trap of simply saying "how can you possibly not see things just the way I do??" that I laugh at others for (at best)

no harm meant, I'm just imperfect.

peace

Pam

Marshall-

I feel now I'm overreaching the bounds of etiquette, posting so many times in a row without reply, but hopefully this is the last.

I was really having trouble with the imagery of submission, and brought it to the nontheist friends list, where I got some great insights.

I still think that it's the wrong way for me to approach it, but I understand better how it works for you and others.

As I mentioned on Zach's blog, I think it can be tied to gender and sexism and feminism. As Zach paraphrased, (attributed to some unknown theologian) Men often need to overcome the sin of pride, and women often need to overcome the sin of not enough pride.

It strikes me when various people, including you seem to respond to my declarations that I don't feel submissive to god as if I am therefore putting myself at the center of the universe. It would never occur to me to do so. Just because I don't think God weighs the evidence and decides if I should wake up each morning doesn't mean I think I have any control over that! I think that for some, humility is so built in that making it part of religion is fruitless.

So it may not be so much about not being willing to be submissive, but not having to work at it. What I have to work at is being spiritually active - accepting myself as an agent. Accepting that it's possible that it matters what I do. It's simply a very different perspective.

peace!

Pam

Jay, thank you for your kind words. You know it wouldn't have happened if you hadn't spoken out first!

Pam, I appreciate your lavish feedback. There's so much of it, I'll only be able to respond to a few parts of it. I'll start work on a reply some time later this morning.

Hello, Pam.

Yes, you and I have strong commonalities, which I honor in the fact that you are listed on the "Kindred Souls" page of this site (always accessible from the control panel at left).

On the other hand, despite our commonalities, and despite the fact that we are both involved with the Religious Society of Friends, I am not sure that we are true co-religionists.

I do not say this as a rejection of you; I would never reject you. I am simply stating a fairly obvious fact.

You write, "...one CAN serve the truth (that's a phrase that I've certainly heard)...."

Yes, I've heard it, too.

But what sort of "service" is it, when truth is so subjective a thing? As I observed in my earlier response to you, above, "no relationship can be truthfully described as a waiting relationship, if the one supposedly being 'waited upon' is incapable of putting the waiter or courtier to any test by expressing unexpected desires at unexpected moments. And truth and reality, being abstractions rather than people -- and observer-defined abstractions at that! -- are incapable of putting the waiter to such a test. They cannot unexpectedly send the wine back because they don't like it, or unexpectedly change their minds about which entrée they wish to order. Jesus can do such things, God can do such things, but truth and reality cannot."

There is also what happened to Saul on the road to Damascus -- which happened to me, in a somewhat milder form, in 1970, outside the steps of St. John's Cathedral in New York City -- and has also happened to many others, down through human history. Mere abstract truth cannot do that, either.

You write, "I tend to think of that as a very quakerly way to look at things - that one can participate in God (as a verb, like love) rather than just serving 'him'...."

Now, I'm not entirely sure what you mean by "participate in God (as a verb, like love)". As Paul told the Athenians, "in Him we live and move and have our being", so that even disbelievers and people who have no intention whatsoever of coöperating with Him (Her), still participate in Him (Her) willy-nilly.

But I don't think that taking "participation in God" as being somehow an acceptable alternative (even a desirable one) to serving Him (Her), is a "very quakerly way to look at things".

The path of serving God -- the path of obedience to God in all things -- has been treated by Friends as the very highest path a person could take, from the very beginning of Quakerism down to the present. Friends honored many of their weightiest members by republishing their writings, after their death, in volumes whose titles described the author as "that servant of God, So-and-So". (Thus the volumes of works by Elizabeth Stirredge, William Dewsbury, John Banks, John Richardson, John Gratton, and George Whitehead, among others.) They didn't say "participant in God"!

Friends rebuked secular authorities who demanded that they obey laws contrary to conscience by quoting Peter's famous words, "We ought to obey God rather than men." Note the "obey". And they upheld their peace testimony by quoting Christ's words to Pilate that, "If my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, but my kingdom is not from here." (Note the word "servant".)

George Fox wrote in 1676, in his letter defending the equality of women with men within the Society of Friends: "...[The Lord's] spirit being poured upon all flesh in the christian times ... this is his spirit, by which all should profit in the things that be eternal, and to serve God in the spirit, both men and women, sons and daughters...." (Emphasis mine.)

Isaac Penington wrote in one of his letters (undated) explaining Quakerism, "The gospel is the power of God unto salvation; it is the glad tidings of freedom from sin, of putting off the body of sin by the circumcision and baptism of the Spirit, of being delivered out of the hands of our spiritual enemies, that we may serve God ... in holiness and righteousness all the days of our life." (Emphasis mine.)

William Penn wrote in his best-known book, No Cross, No Crown (1682), that "There is a lawful and unlawful self, and both must be denied.... The children of obedience, with holy Paul, count all things dross and dung, that they may win Christ, and know and walk in this narrow way. Speculation will not do, nor can refined notions enter it.... They that do my Father's will, says the blessed Jesus, shall know of my doctrine; them he will instruct. There is no room for instruction where lawful self is lord and not servant. For self cannot receive it...." (Emphases mine.)

William Dewsbury, in his celebrated sermon on Quakerism at Gracestreet church, shortly before his death in 1688, described the condition of the Quaker thus: "[Such] a man is not lifted up in his own mind, but laid low in his own eyes: he waits for the wisdom of God to govern him.... He is as contented with bread and water, as with all the enjoyments of this world.... His own will is gone, and put under his feet with whatsoever gives life to his vain desires and affections. There is a harmony of all within, a man praising God, and blessing his holy name. No entanglements shall draw away the heart from serving God and seeking his glory...." (Emphasis mine.)

John Woolman wrote of his convincement as a Friend, "I was ... led to look seriously at the means by which I was drawn from the pure Truth, and learned this: that if I would live in the life which the faithful servants of God lived in, I must not go into company as heretofore in my own will, but all the cravings of sense must be governed by a divine principle." (Emphases mine.) He wrote of his middle years, "...Sometimes when the prospect of the work before me has been such that in bowedness of spirit I have been drawn into retired places, and besought the Lord with tears that he would take me wholly under his direction and show me the way in which I ought to walk, it hath revived with strength of conviction that if I would be his faithful servant I must in all things attend to his wisdom and be teachable, and so cease from all customs contrary thereto, however used amongst religious people." (Emphasis mine.)

Many prominent modern Quaker writers have used the language of servanthood to describe the essence of the Quaker path. A quick look through my library reveals such passages in the works of Paul Lacey, Hugh Barbour, Richard J. Foster, and Sandra L. Cronk -- and I am sure that this is just scratching the surface.

On to other matters. You write, Pam, "You point out that it's an act of ego or judgement for me to say that Jesus wasn't perfect, and who set me up as judge and jury anyway? I was, however, responding to a perception that you believe that Jesus is/was perfect (am I wrong?) which is, for better or worse, equally egotistical."

But Pam, I don't judge Jesus as perfect or as imperfect. Judging him one way or the other doesn't interest me, any more than judging my wife one way or the other interests me. My relationship with Jesus is not one of passing judgments on him, whether favorable or otherwise.

Further down you write, "You make proclamations about how God is (he decides whether or not I will wake up tomorrow morning, etc) with no reference to yourself -it's not that you believe that, it's that it's TRUE." Indeed I do. I see no reason to speak about the truth in any other way.

I don't bother to say, "I might be wrong, but I personally think all triangles have three sides," when it is perfectly obvious that all triangles have three sides. Were a shape not three-sided, then by definition, it would not be a triangle. And were God not omnipotent, in control of all things including whether or not you and I wake up each morning, then by definition, He would not be God.

Please don't expect me to add "maybe I'm wrong" when I'm pointing out things that are tautologically true.

And this brings us to your concluding pair of questions. First, you write: "I am left with a question about what you perceive God's will to be. Does God always will the greatest good? The greatest kindness? The fairest outcome?"

The Christian answer (with which I concur) is, Yes. This is where, as far as I can tell, Christianity differs from all the other great monotheisms. Judaism's God may direct the slaying of Amalekites whose only crime was being brought up to believe in some other religion. Islam's God may be heartless toward those who are not "people of the Book". Sikhism's God may demand crazy sacrifices for a guru just to prove one's loyalty. But Christianity understands God as being the One who teaches us what love is in our hearts and consciences, and having come to that insight, it sees that the character of God is such that He never wishes anything but the best in this world for all His children and creatures.

"For everyone who asks receives, and he who seeks finds, and to him who knocks it will be opened. And what man is there among you who, if his son asks for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for fish, will he give him a serpent? If you then, being sinful, [yet] know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good things to those who ask Him!" (Thus, Christ in Matthew 7:8-11.)

And then, you write, "...If that is true, what if we take that out of the equation and serve it directly. Rather than doing God's will, because we assume it to be for the greater good (for example), why not serve the greater good directly? (or serve life, human dignity, love, compassion, justice, directly) ... I believe that there is a spiritual component to discerning how best to serve these...."

My answer is, if we were sinless -- never overcome by our own selfishness, or by our own insecurity and defensiveness, or by our own irritability and tendency to lash out, or by our own purblindness and poor judgment -- then such an approach would work. But it is precisely because we have such shortcomings that we must listen to the conversation Partner who can guide and correct us into what is truly good. This is in fact the age-old teaching of Christianity, which the Quaker movement restored to its original virtue by restoring people's attention to God's presence as Teacher in our hearts and consciences. And the fact that I agree with it is the reason why I am a Friend.

Pam, you write that I "seem to respond to [your] declarations that [you] don't feel submissive to god as if [you are] therefore putting [your]self at the center of the universe."

That's not what I said to you, Pam, and it's not what I meant.

What happened is this. You raised the issue of giving up one's ego, and said, you didn't believe that it's impossible for a person to do so unless the person is giving it over to another. I responded by pointing out that regardless of what your theory of ego-shedding may say, the observable facts suggest that you might not yet be ego-free, and that this lack of complete freedom from ego just might, perhaps, be connected to your reasons for objecting to the theology of servanthood.

(And I said, I'll leave it to you to decide what the truth of the matter is. I don't know you, and even if I did, I'd be very reluctant to judge you.)

Even if you're not free of ego, that's not necessarily the same thing as putting yourself at the center of the universe. There are, surely, forms in which the ego manifests that are very different from putting oneself at the center of the universe -- being burdened with the feeling that "I'm not good enough," for example. When Moses said to God, "I can't face down the ruler of all Egypt; I'm a lousy public speaker" -- Exodus 4:10 -- he was letting his ego, which is to say his sense of self, get in the way of obedience. Any condition in which "I" keeps getting in the way of God, whether the "I" in question is perceived as great or as inadequate, is a form of I-ism, egoism. Does this make sense to you?

I also suspect that you're using the terms "submission" and "submissive" in a different way from me. I'm not talking about submission to other people; I'm talking about submission to that Voice that shows us the right and loving thing to do. Sometimes the right and loving thing to do is to stand up and show some backbone! And in such cases, submission to God may not look like submission at all in the eyes of the person you are confronting.

Perhaps it's God who is telling you that it matters what you do. Have you explored that possibility?

Amazing series of comments here.

I think it was Augustine (a non-Quaker I must admit) who said that the greatest good, and the only truly intrinsic good was God the Trinity. If that is true, then perhaps serving the greatest good and serving God are the same thing in the end.

It seems to me that Christians and non-theists may be equally surprised on that day the scriptures call judgment day.

Augustine was no doubt echoing Mark 10:18 / Matthew 19:17 / Luke 18:19, where Christ is quoted as saying, "No one is good but One, God."

This, however, is no guarantee that in serving what we think to be the greatest good, we are serving God. We can so easily be mistaken!

The historic Quaker testimony is that the one safe course is direct obedience to the guidance of the Voice in our hearts and consciences (because that Voice is plainly from God), and that all else is "notions". By that standard, serving what we think to be the greatest good, and serving God as we think God is to be served, are equally notional, and equally hazardous.

I guess I have no idea what will happen in the day of judgment. I would say, though, that in one sense the day of judgment seems to me to be happening continuously; we can feel it happening, in the place of conscience.

Thanks for commenting, david!