(click here to go back to the beginning of the essay)

V. Struggles with the New Form of Slavery

George Fox may have had glimpses of the new rising demonic power of plantation slavery as he passed through Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas in 1672 and 1673.

From the evidence of his journal, though, it seems probable that he had little if any exposure to it. The journal is entirely occupied with accounts of brief visits to communities of Friends scattered across the vast coastal wilderness, and with the difficulties his party experienced making its way through that wilderness.

For whatever reason, there are no mentions of slavery in Fox’s account of that journey at all.44

Nonetheless, as the outlines of slavery’s new form emerged, and as Friends who actually lived in the New World were present to see, they began calling on their Society to face the facts and reject the new evil.

This process started with gratifying promptness. We’ve already seen, in the first installment of this essay, how Germantown Friends spoke out against slavery in 1688, just four years after Pennsylvania was founded.

In 1696, eight years later, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting issued a recommendation that Friends not encourage the importing of slaves.45 The fact that the concern evolved from one expressed by just a handful of Friends in 1688, to one expressed by the whole yearly meeting eight years later, suggests that most of the community must have begun pondering what they were seeing, and feeling uncomfortable about it, during that eight-year period.

Why did Philadelphia Yearly Meeting speak only against the importation of slaves, and not against slavery as a whole? Some modern Friends have expressed a belief that it was because Philadelphia Yearly Meeting was not yet ready to recognize the evil of slavery itself. The truth, however, was more complex.

Once again we must bear in mind that Friends came out of England, where agrarian doulos-slavery had been gentled into villeinage (and the villeins, or serfs, had subsequently been granted “freehold”, leaving them still exploited peasants, but ending their serfdom), and domestic doulos-slavery had been gentled into “free” servanthood. No country in all of continental Europe had first owned slaves and then gentled the institution so. Friends had taken this model of a gentled slavery as the one to which they expected all slaveholding to conform.

Certainly the Quaker leadership had done their best to commit the Society of Friends to follow this model with any black slaves its members owned. Thus, when William Penn set up a voluntary association of Quaker merchants, the “Free Society of Traders” in 1682, and permitted them to own slaves, he expressly stipulated that if they did this they “should make them free at fourteen years end.”46

A 1738 advertisement in Philadelphia’s American Weekly Mercury, offering slaves for sale. The iconic art both depersonalizes the slaves and denies their sufferings. (From Common-place: Walking Moraley’s Streets: Philadelphia [www.common-place.org, vol. 3 no. 4, July 2003].)

And the majority of slaveholding Friends in Pennsylvania and New Jersey do seem to have managed to adhere to a fairly gentle and limited form of slavery — or at least, to a much more gentle and limited form than prevailed in the colonies to their south.47

Finally, we might note that 1696, when Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting issued its advice against the importation of slaves, was exactly fourteen years after Penn made his stipulation to the merchant society he’d founded. So it had not quite come to the point yet where Friends would be disillusioned by the way their slaveholders kept postponing the manumission of their slaves.

So at this point, most Pennsylvania Friends still felt it was reasonable to expect that the form of slavery practiced among Friends would work out well in the end, bringing the Africans to Christianity and civilization and empowering them in the process, until ultimately it freed them along the lines laid down in Paul’s letter to Philemon, while in the mean time providing profit for their owners.

But enough of these same Friends had seen something of the nature of the slave trade — even in their own city of Philadelphia — and of slaveholding in Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and above all the West Indies, to know that neither the slave trade, nor slaveholding in the southern regions, followed any worthy pattern. They had some sense by now of the wrongs through which Africans came into the hands of slave-traders. And they knew that, in the big-plantation portions of the Deep South and the West Indies, there was a norm already emerging to the effect that it was acceptable to work slaves to death for profit.

And the painful fact was, Quaker slave-traders were no better than non-Quaker slave-traders. They too dealt in captives who’d been wrongly enslaved — and they knew it, since they bought them in Africa, where they could see the wrong beginnings for themselves. Likewise, they sold the slaves they imported to whoever would buy them, not just to compassionate and enlightened Quaker owners. In fact, the vast majority of the hundreds of thousands of African slaves imported to the British New World during this period, by Quaker and non-Quaker slave merchants alike, were sent to the West Indies, where they generally soon died of malnutrition and overwork.48

Thus, in the eyes of most Friends in Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting in 1696, Quaker slaveholding might not yet be clearly in the wrong, but the slave trade was a fully-proven evil.

As the seventeenth century aged into the eighteenth, more and more Friends became convinced, not only that Quaker slaveholding was not the institution George Fox had wanted it to be, but, indeed, that it might not be capable of ever becoming humane.

For New World slavery was not, like doulos-slavery among early Pauline Christians, merely the lowest form of employment, from which one could rise to better things by being worthy; even under Quaker slaveholders, it was a reduction of worthy, feeling human beings to the status of mere property, to be exploited in whatever way the owner pleased, without any sure hope of obtaining freedom — at least, this side of death.

And as more and more Friends became convinced of this, the number who could countenance slavery of any kind, dwindled steadily. And the nature of the criticisms that would-be Quaker reformers expressed, regarding the practice of slaveholding, began to change.

In Fox’s time, Friends had simply expressed opposition to all abuses of servants and slaves. This was still the position of most of the anti-slave-trading activists in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting.

But in the late seventeenth century, second- and third-generation Friends began saying slavery was innately wrong, and had to be ended altogether. The Irish Quaker minister William Edmundson was the first to do so, in the course of a visit to slaveholding New England in the late 1670s.49 Shortly after, Friend George Keith published the first American book against slavery, following his own encounter with it Pennsylvania.50 Germantown Friends spoke out in 1688, Keithian Friends in 1693, and Friends in Chester County from the mid-1690s onward.

By the second decade of the eighteenth century, abolition had become a consuming crusade for a handful of fourth-generation Quaker ministers: William Southeby, James Farmer, William Burling, and John Hepburn.

It’s significant that, of these four early abolitionists, three were born and bred in the New World, and the fourth, James Farmer, was an Englishman who came to the anti-slavery position only after coming to the New World. It was, after all, the special features of New World slavery that inspired abolitionism.

Alas, these Friends swiftly encountered opposition from the slaveholding Friends themselves.

Samuel Fothergill, who came a generation after these pioneers, described the roots of this opposition thus:

Their fathers came into the country in its infancy, and bought large tracts of land for a trifle; their sons found large estates come into their possession, and a profession of religion which was partly national, which descended like the patrimony from their fathers, and cost as little. They settled in ease and affluence, and whilst they made the barren wilderness as a fruitful field, suffered the plantation of God to be as a field uncultivated, and a desert. …

A people who had thus beat their swords into plough-shares, with the bent of their spirits to this world, could not instruct their offspring in those statutes they had themselves forgotten.51

In other words, the problem lay with the fact that Friends had arrived in the middle colonies as a mixed multitude: most of them, truly converted Christians who’d been humbled by the Voice they’d met in their hearts — but some of them, “grandees” who’d come with hearts untransformed, meaning to live as splendidly in the New World as in the Old — and others, yeomen who’d come hoping to build businesses and prosper, and who saw cheap slave labor as a means to that end.

Invested as these two latter groups were in the ruling-class life, they had little desire to honor the equality of all humankind, blacks alongside whites. And they did not teach any better values to their children; nor did most of their children learn better values on their own.

It became a series of power struggles between the anti-slavery idealists and their opponents.

When the Quaker abolitionists William Southeby and James Farmer campaigned against slavery in the 1710s, rich Friends initiated proceedings against them: Southeby was disciplined in 1716, and Farmer disowned in 1720. In the 1730s, when Philadelphia Yearly Meeting asked its member quarterly meetings whether Friends should be forbidden to buy slaves, the poor rural quarters all said yes, this should be done, but the wealthy friends in the rich urban quarters stood against the reform and successfully prevented any progress until 1743.52

Frustrated by the wealthy Friends’ obstruction, the anti-slavery agitators refined their arguments to eloquence. The refinement is already apparent in John Hepburn’s 1713 anti-slavery tract, which (as Hugh Barbour and J. William Frost have summarized it), “[s]eeing the cause of slavery as greed, attacking a belief that human beings could be considered property, mourning the discrepancy between profession and activity … denounced slavery on a basis of Quaker beliefs, scriptural exegesis, personal knowledge of the cruelties involved, and natural rights.”53

By the 1720s, the message of abolition had reached the hearts of an entire class of devout fourth-generation American Friends. In the 1730s, all the Quaker slaveholders of places like Shrewsbury and Rahway, New Jersey, were freeing their slaves in their wills — every blessed one of them. And in the 1730s the fifth-generation Quaker abolitionists were beginning to find their voices: first Elihu Coleman, then Ralph Sandiford and Benjamin Lay, and ultimately John Woolman and Anthony Benezet.

At this point, in their frustration at the slaveholders’ continuing obstructivism, the abolitionists were becoming quite strident. Of course, there’d already been a strident note in Hepburn’s 1713 tract, with its talk of greed and its innuendos of hypocrisy. But that was nothing compared to Benjamin Lay’s witness at Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1738.

Lay arrived at Yearly Meeting wrapped in a cloak, and when the meeting was fully settled into worship, he rose to his feet, denounced slavery, and threw off the cloak dramatically to show that he was wearing a military uniform, complete with sword, underneath. He declaimed, “Oh, all you negro masters who are contentedly holding your fellow creatures in a state of slavery during life, well knowing the cruel sufferings those innocent captives undergo in a state of bondage … you might as well throw off the plain coat as I do…. It would be as justifiable in the sight of the Almighty…. You … thrust a sword through their hearts as I do through this book!” And drawing his sword, he thrust it into a book which he had previously hollowed out and filled with a bladder of red berry juice. The “blood” splashed out on his fellow-worshipers —54

Such antics were guaranteed to alienate the snobbish Quaker slaveholders. Lay was disowned — expelled from the Society of Friends — by those whom he’d offended and embarrassed, that very year.55

VI. Woolman, Benezet, and Tactics that Worked

Matters in the Society of Friends in the middle colonies had arrived at a point of crisis. Those who were readiest to hear criticisms of slavery had already been reached and converted, and were (for the most part) quite ready now to ban it altogether.

But the entrenched core of wealthy and privileged slaveholders, and their allies in the slaveholding artisan class, were still resisting the call to face the facts of slavery — for much the same reasons that modern industrialists and middle-class Westerners resist the call to face the facts of global warming today.

Eloquence and stridency had failed to reach them. Some other method was needed.

And so it was that John Woolman, the best of the next generation of abolitionists — and his allies Anthony Benezet, John Churchman, Samuel Fothergill, Israel Pemberton, Jr., and others — were led to reach back into history, and to reclaim the methods of the prophet Nathan, Jesus Christ, George Fox and the first Friends.

What? Reclaim the methods? Wasn’t Woolman the creator of those methods? — No, he was not.

Modern historians do often speak of Woolman as if he invented his methods for reaching slaveholders’ hearts out of thin air — just as they often speak of him as if he were the very beginning of Quaker abolitionism. But Woolman merely took up methods that had been practiced in well-known ways by prominent Friends all through Quaker history, and applied them to a new issue.

There were four important components to Woolman’s methodology. And the first of these, the one most commonly remarked on, was his practice of visiting wrongdoers privately, so that he could labor with them in settings where they wouldn’t be worried about appearing wrong or weak before their fellows.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that Nathan took this same approach in his Old Testament confrontation with King David.56 I would add here that whether Nathan actually did so or not, Christ most definitely institutionalized the private approach as a part of church discipline in Matthew 18:15-17; George Fox and William Dewsbury made it the mandatory first step in resolving disputes among Friends;57 John Roberts, the charismatic Robin Hood of early Quakerdom, made use of it in his confrontations with the powerful men of his home district;58 and Joseph Pike and his co-laborers relied on it in their reform of Irish Quakerism during the 1690s.

The second important component of Woolman’s method was the extraordinary meekness, gentleness and patience with which he dealt with the people he was trying to bring around. It was an absolute reversal of the stridency of earlier Quaker abolitionists, and it was so effective in Woolman’s hands that, even in his own lifetime, many of his contemporaries came to see him as a saint.59

Yet this same meekness, gentleness and patience had — again — been made a mandatory part of the Quaker approach to eldering by Fox, Dewsbury, and the elders of Balby,60 and had been put into practice in a very impressive way by Joseph Pike and his co-laborers.

Let us pause, therefore, at this point to take especial note of two of these precedents: George Fox’s advice to Friends in his letter 264, written in 1669, and Joseph Pike’s description of the methods that he and his co-laborers used.

Fox wrote, in part,

…All such as behold their brother or sister in a transgression, go not in a rough, light or upbraiding spirit to reprove or admonish him or her; but in the power of the Lord, and spirit of the Lamb, and in the wisdom and love of the Truth, which suffers thereby, to admonish such an offender. So may the soul of such a brother or sister be seasonably and effectually reached unto and overcome, and they may have cause to bless the name of the Lord….

This is the very principle that Woolman followed, and we see it here spelled out plainly — and its power recognized! — three generations before Woolman began his work.

And now here is Pike’s account of how he restored the discipline of simplicity to errant Friends in Ireland:

Having … cleared our own houses and families of superfluities, as we thought the plainness of Truth required, we then proceeded to visit others, and the method of our procedure was thus.

We first met together, being six or seven in number; and after waiting for a time in silence upon the Lord, every one, as he found it on his mind, spoke what appeared to him suitable on the occasion; and in a tender, brotherly manner, every one of us freely submitted ourselves to one another; how far, each stood clear as to life and conversation and other matters: as also, whether we ourselves had complied with the rules of the Society. For in our conference together, we told one another, that if we were not good examples ourselves, we were not fit to advise others: and in our discourse, we were very plain and free with each other in the love of God.

I can say of a truth, our hearts were greatly humbled before the Lord, under a sense of the great weight of the concern, and our own weakness and unworthiness for such a service; yet as we were appointed thereto, and with a deep concern of mind for the prosperity of Truth, and the welfare of those whom we were to visit, we proceeded accordingly, and visited every Friend’s family, and those who attended our meetings in the city of Cork.

In doing which, we first sat down with them together; and as we found a concern to come upon our minds, suitable to their respective states and conditions, we gave them advice and counsel, &c.; and particularly to keep close to the witness of God in themselves, the gift and measure of his Holy Spirit, by which they might come to know and experience a growth in the Lord’s holy Truth, whereby the inside would be made clean, and then the outside would be made clean also.

After we had spoken what was in our minds relating to spiritual things, we then proceeded to other things relating to conversation and behaviour, &c., as occasion offered. Then we read sundry rules of superior meetings, and spake the needful to those rules and advices, without partiality to any.

And I can in great humility of mind say, the Lord owned us in our service by the attendance of his living presence, which in several places broke in upon our spirits and some of theirs also, bowing their hearts into great tenderness.

Some who had not been so faithful to Truth, nor so orderly in their conversation as they ought to have been, were so reached by what was spoken, that in much brokenness of mind, they acknowledged the same, with desire that for the time to come, they might be more faithful to the Lord, and walk more circumspectly. And indeed we had very melting seasons in many places, all which greatly strengthened and confirmed us in our service and labour of love; and I do not know that we met with any opposition or stubbornness in all the places we visited, but a general condescension in all, to put away superfluities in apparel and household furniture, which was accordingly done some time after.

So that there was a pretty thorough reformation in this city as to things that appeared contrary to Truth and the rules of the Society.61

Anyone who has studied Woolman’s own life and writings will recognize at a glance that this was the same thing he did with the slaveholders.

The remaining two components of what Woolman and his allies began doing were speaking directly to the compassionate part in the slaveholder, and calling the slaveholder’s attention to the crucial facts and truths of the situation.

By way of illustration, let me cite two passages from John Woolman’s Journal.

The first quotation shows Woolman evoking his hearers’ awareness of the gap between the English ideal for servanthood and the way American slavery had actually turned out. Notice, please, the words I’ve italicized in this passage, which underscore the gap between the ideal and the reality. And notice, too, the way in which the passage as a whole very gently and compassionately turns on those words:

…A Friend gave me some account of a religious Society amongst the Dutch, called Minonists [Mennonites]…. One of the Minonists having acquaintance with a man of another Society at a considerable distance, and being with his wagon on business near the house of his said acquaintance, and night coming on, he had thoughts of putting up with him; but passing by his fields and observing the distressed appearance of his slaves, he kindled a fire in the woods hard by and lay there that night.

His said acquaintance heard where he lodged, and afterward meeting the Minonist told him of it, adding he should have been heartily welcome at his house and from their acquaintance beforetime wondered at his conduct in that case.

The Minonist replied: “Ever since I lodged by thy field I’ve wanted an opportunity to speak with thee. The matter was, I intended to come to thy house for entertainment, but seeing thy slaves at their work and observing the manner of their dress, I had no liking to come to partake with thee.”

He then admonished him to use them with humanity, and added: “As I lay by the fire that night, I thought that as I was a man of substance, thou would have received me freely, but if I had been as poor as one of thy slaves, and had no power to help myself, I should have received from thy hand no kinder usage than they.”62

The second quotation shows Woolman pointing out the gap between the real motives of North American slaveholders and the Pauline ideal. Notice again how this passage relies on compassion:

…I … replied: “If compassion on the Africans in regard to their domestic troubles were the real motives of our purchasing them, that spirit of tenderness being attended to would incite us to use them kindly, that as strangers brought out of affliction their lives might be happy among us….

“But … we manifest by our conduct that our views in purchasing them are to advance ourselves, and … our buying captives taken in war animates those parties to push on that war and increase desolations amongst them….”63

Meanwhile, Friend Anthony Benezet, a contemporary of Woolman, was horrified by the growing white belief that Negroes were congenitally inferior to Europeans and, as such, not fit for a life of freedom and equality.

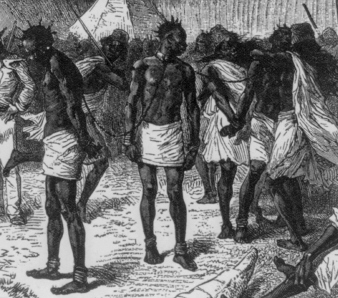

Captives in an African slave market, being sold to white slave traders. Note the emotion — the very thing that the depersonalizing art in the newspaper ad, shown in the previous section of this essay, concealed. (Library of Congress)

This development distressed him, not only because it offended his gut sense of the equality of all humankind, but also because it sabotaged the ideas of “uplift” and “ennoblement” — the idea that a master could uplift his slave and fit him for freedom, and the idea that the slave would thereupon become the master’s full equal. Thus, as the idea of permanent Negro inferiority caught on, the possibility of making slavery a transitory institution leading to the Negro’s full equality in white society, would recede and disappear.

And so, in 1750, Benezet opened a school in his own home for poor Negro children — the first such school in all North America. He taught the children there for twenty years, creating a full generation of Negro scholars whose attainments and lives contradicted the myth of racial inequality. And he was then able to testify from his own direct personal experience to his fellow whites:

I can with truth and sincerity declare, that I have found amongst the negroes as great a variety of talents as amongst a like number of whites, and I am bold to assert, that the notion entertained by some, that the blacks are inferior in their capacities, is a vulgar prejudice, founded on the pride or ignorance of their lordly masters, who have kept their slaves at such a distance, as to be unable to form a right judgment of them.64

Much like Woolman’s methods, Benezet’s way of proving that “different” sorts of people were equal to his own was not original. It had been anticipated by George Fox himself, in Fox’s public interviews with Native Americans, in which he showed skeptics that the Indians, too, had a conscience and a living Instructor within them.65

So in every respect, Woolman and Benezet were not pioneers. They were not introducing “new truths” or “new revelations” to replace a benighted older form of Quakerism. They were rather adapters of old methods, in support of an age-old set of values, but in response to an evil whose changing shape now urgently demanded such adaptations.

Woolman, Benezet and their associates saw what Joseph Pike and his associates had seen before them (and Francis of Assisi even earlier, and Nathan even before that) — that, in order to break people free of an evil in which they are deeply involved, it is necessary to labor with them, face to face, often privately, and if need be one person at a time — speaking, moreover, as much as possible from concrete personal experience of the things the opposition was closing its eyes to. No method of getting through to chronic sinners can succeed unless the person trying to get through is willing to get down-and-dirty with them, in the same way that Nathan did with King David.

I think this must have been an unwelcome truth for many eighteenth-century Friends. For getting down-and-dirty with wrongdoers is taxing, inconvenient, and risky; it eats up one’s time, and there’s sometimes physical danger involved. And Friends were busy people, then as now; they’d have preferred to keep their time their own.

But once the Society of Friends had faced up to the lesson, it took it utterly to heart. Jack Marietta, in his account of the eighteenth-century self-reformation of American Quakerism, tells us that in the course of that reformation, after Woolman showed the way, “no one was visited more often than the slaveholders, especially in the 1760s.” And Marietta would know, because he actually compiled the numbers.66

(to be continued soon)