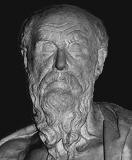

It’s not entirely clear what Herakleitos, the ancient Greek philosopher, meant by “Logos”. But he was the first to use the term.

And the reason it appears in the Gospels of John (“In the beginning was the Logos … and the Logos became flesh, and dwelt among us…”, John 1:1,14) and Luke (“The Seed is the Logos of God…”, Luke 8:11), ultimately goes back to Herakleitos.

Why do I bring this up? It’s because I’m exploring, in this blog, what traveling in the ministry is about. And it’s a real basic fact that what a minister does — whether traveling or not — is ultimately all about the Logos. She, or he, seeks to be a good imitator of Christ, sowing the Seed. Early Friends were quite clear about this.

So what is the Logos? To say it is Christ, merely begs the question. John told his readers that Christ was the Logos because his readers knew Greek and knew something of Greek culture; knowing something of Greek culture, they knew how Herakleitos and his heirs used the term; knowing how Herakleitos used the term, they had some idea what Logos meant to John. Having some idea of what Logos meant, it helped them understand who Christ was. To say that the Logos is Christ is useful if you have such an independent understanding of Logos, but it is a rather empty statement otherwise; if his readers hadn’t had some grounding in Greek culture, John might as well have simply saved his breath.

So there is some point to trying to understand what Herakleitos, and his followers, understood by “Logos”. It might help us see Christ, as John understood him, a bit more clearly; and it also might us help see what the minister should — and should not — be doing, more clearly.

Now, one interesting thing about the meaning of Logos in Herakleitos’s own time is that most Greeks back then were illiterate. And being illiterate, they had never learned the idea that a “word” is a discrete unit of speech, something set off from its fellow words by the use of spaces between them. In fact, those Greeks who could actually write didn’t put spaces between their words on the page; they just ran them together, as if they were all one word. And the Greeks would describe the writing as a whole — everything on the page lumped together — as a “word”. “We have a word from Euripedes” (or whoever), someone would say, waving the sheet in the air.

So Logos, even before Herakleitos got to it, didn’t simply mean a particle of speech. It meant the bigger thing — a communication, a burst or web of meaning.

But “Logos” was still an ordinary word until Herakleitos got to it. And then he took it, and began talking about the complexities of meaning — about how profound, mysterious, and self-enriching, and utterly amazing in its workings, meaning can be.

Herakleitos didn’t talk about small-l logos — any old burst of meaning. He talked about Logos as a capital-L — the cosmic web of meaning, the Ultimate Web That Weaves It All Together. And Herakleitos said:

Wisdom is one thing — to know the thought whereby all things are steered through all things.

— In other words, wisdom is to know the logic by which God shapes the world —.

This Logos [wrote Herakleitos] is eternally true. Yet people remain as uncomprehending of it, after they have heard it once, as they had been before.

In other words, most people are pretty clueless, and that is a hard thing to fix. I can’t help thinking of all the difficulties Christ had, getting his teaching across to his disciples!

And failures of understanding lead to shallow judgment — as Herakleitos said,

Asses would prefer straw to gold.

Or in Christ’s version, “Pearls before swine…”!

But why do people have so much difficulty in understanding? Here Herakleitos answered by pointing to the subtleties of reality. For one thing, he said, things are always changing, so that if you rely on the same old ideas about what is, you are likely to miss the changes and get yourself into trouble:

You cannot step twice into the same river, for other and still other waters are continually flowing through.

Into the same river we step — and do not step….

Our only hope, therefore, is to let go of rigid thinking and be open to new guidance —!

And then there is the fact that things can conflict in ways that are fruitful and produce higher harmonies. As Herakleitos put it,

They fail to understand how a thing can be at odds with itself and at the same time be in agreement with itself. Yet a tension resisted can make a synergy or harmony — as in the bow and the lyre.

And of course, the Crucifixion was itself such a fruitful conflict. As also are many of the initial disagreements in our meetings for business, that lead us through the process of corporate discernment into higher wisdoms. Indeed, the whole world works a lot like this:

The harmony of the whole world is of tensions, like that of the bow and the lyre.

Whether we like it or not, it is often only through such painful beginnings that we grow in the ways that matter —

Every beast is driven to pasture with blows.

But the wisdom gained thereby is precious. Through such seemingly discordant beginnings, the Logos reveals itself — the divine meaning that makes sense of the Universe. As we glimpse the Logos, the cosmic sense, we find that it is everywhere, accessible to all of us, indeed embedded in all of us.

The Logos is common to all….

The problem is that, since the path to glimpsing the Logos comes through that painful path (which we Christians sometimes call the path of the Cross), people shy away from it, choosing self-protection and self-enrichment instead, and trying to give the Universe a meaning built on self-protection and self-enrichment instead of its true meaning —

We should let ourselves be guided by what is common to all. Yet, although the Logos is common to all, the general run of people live as though each had his own special cleverness [ídia phronésis].

They are at odds with the very thing to which they are most constantly connected!

Is this a true understanding of Herakleitos’s meaning? It’s hard to say, because all that survive of Herakleitos’s writings are fragments, and the fragments can be interpreted in other ways.

But it may be significant that one of the first great Christian theologians, Justin Martyr, described Herakleitos as a true Christian before Christ. Would preaching the path of the Cross, and the the saving wisdom of the Cross, lead Justin Martyr to describe a philosopher as a true Christian? Would it lead Luke and John to adopt that philosopher’s language?

If I’m right (which is open to dispute, I know), then this is an important clue to how John understood the central nature of Christ, and how Luke understood the central gospel of Christ. And it is also an important clue to what the minister of Christ is called to preach. Remember that the magical synergy of stick and string, in the bow and the lyre, is as much a part of it as the gateway of suffering! The Logos of Herakleitos, which was the Gospel of Christ in Luke 8 if I’m reading these things right, is the path of transformation, on more levels than one.

I have every intention of returning to this topic at a later date. But in the mean time, I’d welcome your comments, whether you agree with me or think I’m full of it.