I’ve been giving this web-journal a break, because I’ve been feeling a strong need to focus on my upcoming presentations at Baltimore Yearly Meeting. But it weighs on my conscience that I haven’t told any of you what to make of my silence, and that some of you may be starting to feel a bit concerned.

For those of you who don’t already know the details — I’ll be finishing my walking-and-driving journey in just one week, on the afternoon of Monday, July 31 (God willing). And from that point on, my life is likely to be something of a whirlwind, what with a Bible study group I have promised to convene, a workshop on witness I have pledged to lead, and of course, the talk I’ll be giving on Saturday, August 5, which this journey has been leading up to.

So this final week of my journey is my main chance to sort it all out, let it all settle, hold my thoughts to the Light of the Inward Guide, and seek to become as unresisting to God’s further leadings as I can.

The country I’m passing through now has been a romantic region to be doing this in. Yes, there have been blah spots — the journey by divided highway from the campground near Coolville, Ohio, into Parkersburg, West Virginia, and beyond, almost to Cairo (“Kay-ro”), West Virginia, was one. When they put those divided highways in, they destroy so much of the topography of the land, flattening the hills and filling the valleys and pushing away the natural landscape on either side, that it becomes almost impossible to experience what God was actually doing with the place.

The portion of my route on the divided highway that took me out of Parkersburg into West Virginia proper (beginning my four-day climb up the Kanawha River watershed) was particularly painful to me, because here it looked like I was passing through something close to wilderness — hill beyond hill visible from the highway, and nearly all tree-covered — and yet the margins of the road shouldered this seeming wilderness well out of my reach.

I wanted to bury myself in those trees!

But once I turned off the divided highway, onto the little two-lane road that marked the final approach to Cairo, it was all wonderful again. These back-country West Virginia roads wind around the hills and snake through the valleys in a way that really does some honor to the land.

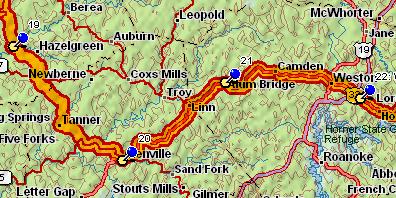

My overnight stop just east of Cairo — the push-pin numbered “18” on the map above, although I actually stayed there two nights, the night of the 17th as well as that of the 18th, doubling back after the first night to walk what I could of the distance I’d just covered — was at North Bend State Park, a very gardened park in which much of the grounds underneath the canopy trees had been cleared of undergrowth and converted to lawn, and a lodge and restaurant, tennis courts, miniature golf, all sorts of stuff I’m not used to seeing in state parks, had been jammed into the landscape.

My tent site was right alongside a creek that flowed wide and shallow and reasonably clear and drew scads of inner-tubing kids, underneath a fifty-foot tree-covered bluff full of nesting birds and their babies. That part was very fine!

But one of the park staffers, after inquiring what I was doing, went out of his way to tell me that neither he nor I nor anyone else can know whether global warming is real or not, because you can find anything you want to believe about the subject on the Internet. This struck me as very questionable logic, but it also struck me that it was his way of fending off a subject he felt deeply threatened by. It made me sad.

From North Bend State Park my route took some magical turns, winding down a back road through mile after mile of woods where almost no traffic went, past three-story abandoned-and-derelict Victorian farmhouses all gauded up with gingerbread in the absolute middle of nowhere. Had I been capable of walking my whole fifteen-miles-a-day, without the aid of a car, I could have spent a half day under the green forest canopy here, walking along, and never seen more than half a dozen human souls in that whole time. But alas, although my feet were doing better and better, I still could not, at that point, walk more than a mile in any given four hours’ time before the serious pain returned.

From Goffs (the push-pin marked “19”) to Glenville (the one numbered “20” on the map below) — I entered an area where tree-cutting, farming and grazing have done substantial damage. Hillsides with slopes of twenty-five to forty degrees — incredibly steep slopes — had been entirely stripped of trees and were now protected by nothing but sparse pasture grass, grazed so heavily that you could see the bare soil everywhere. Ravines were cutting down those slopes, and the creeks at the bottoms of the slope were gullied to a depth of one to three feet — nearly always new gullies, patently still eroding rapidly. Much of the land so stripped had been worked so hard that the grass was brown and weedy brush was replacing it. This is how you convert lush forest to a lunar wasteland, folks.

I spoke with a highway worker on the road south of Burnt House, midway between Goffs and Glenville, at a point where the highway had been temporarily closed to allow a crew to move a big mobile home. He brought up the issue of gas prices without any prompting from me; but for him, as with so many of the people I’ve talked with on this journey, the only possible cause of high gas prices was conspiracy among the gas companies; it was inconceivable to him that there might also be a supply-and-demand situation pushing prices up, let alone that gasoline might some day run scarce.

In Glenville, I shared the motel where I stayed with a huge clan reunion: a family that had lived in the area for generations beyond memory, come together for a long weekend from all over the country. One older, alpha-male-type member of the clan buttonholed me in the parking lot, perhaps having mistaken me for a member of the clan, and when he discovered I’d lived thirty years in Colorado he began reminiscing about the years he’d spent in the oil business in Denver and “um, I think the name of it was Rifle Junction”. “Just Rifle,” I said; “you must have been in the oil shale business.” And so he had been.

Friends, oil shale is a loaded, loaded topic in Colorado. There’s enough oil in that shale to make the Colorado/Utah/Wyoming area a second Saudi Arabia, if they can just figure out an energy-efficient way to cook it out. But oil shale extraction is water-intensive, and Colorado is water-poor; serious oil shale development would bleed enough water out of the already-parched landscape to reduce many hundreds of square miles of it to desert waste. Colorado environmentalists have fought it tooth and nail for decades for that reason.

And the oil in the world’s oil shale reserves is so plentiful that if we burned it all, the carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere would rise to toxic levels; all humanity would die in the same manner as coal miners trapped in a cave. What a thought!

Well, I didn’t say everything I was thinking to the fellow in the parking lot, but he must have seen something in my face, because he changed the topic directly.

It was only after I passed Glenville that I finally began getting the ability to walk some significant distances back. On the journey from Glenville to Alum Bridge (the push-pin numbered “21”), I was suddenly able to walk almost two miles in one go and only suffer mild lingering pain afterward. (Wow, that was a beautiful walk, too. Now the landscape was opening up, the valleys separating each individual hill from the next becoming wide enough to give one a sense of vista, even as the hills grew taller. Tourist country, now.)

Between Alum Bridge and McGuire Park (the push-pin numbered “22”) the countryside filled up with houses and industry, and the highway with trucks, until the final few miles, through Weston to McGuire Park, felt downright urban. It wasn’t easy to do much walking on that stretch, due to traffic hazards. But the following day — yesterday — I could stretch out a bit on the divided highway eastward, and I managed to walk two stretches of two miles each and only suffered a little for it in my ankles that night.

I begin to hope that, by the time I get to Harrisonburg, I’ll at least be able to get around the campus all day unassisted —

In any event, this countryside has been preaching to me, particularly in the lulls between traffic sounds. In those periods of silence, I feel something almost like the living landscape praying for relief from the burdens we humans impose on it:

…The creation waits eagerly, in earnest expectation, for the revealing of the children of God. For the creation was subjected to pointlessness — not willingly, but because of [the first human] who imposed [his own] ambition upon it — [but] the creation itself also will be delivered from the bondage of [this] corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God. …We know that the whole creation groans…. (Romans 8:19-22a)